A recent post on a monorator design has been active. The discussion turned to other ways of drying wood fuel including solar kilns and exhaust gas. Rather than reply there with my exhaust gas idea I’m making my own post because it is long. My use case is a stationary generator, and this idea is cheap but bulky and heavy… not for vehicles! With that caveat:

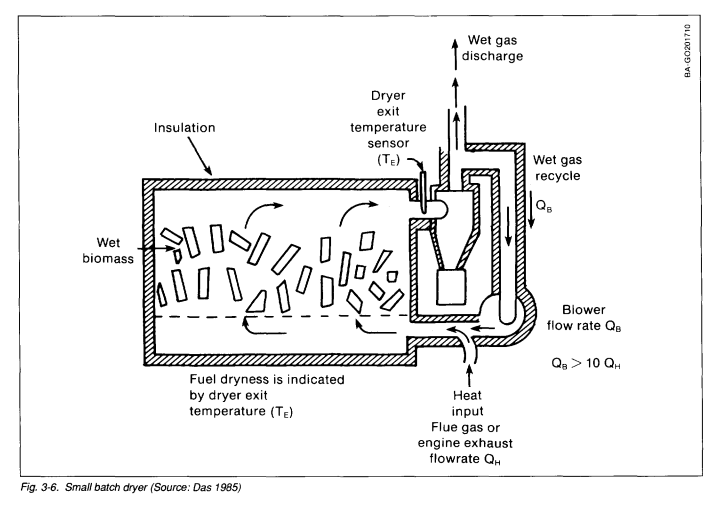

I’ve been kicking around direct exhaust heating/drying of wood fuel. By direct, I mean having the exhaust gas pass through and in between the fuel rather than heating the fuel container like a monorator. There is a lot of heat in engine exhaust but also a lot of water, approaching fully saturated. If you just run the exhaust straight into the fuel charge you get a wet mess (I am told) so it can’t be that simple. On the positive side for exhaust… it is virtually oxygen free which becomes important for drying combustibles as temperatures approach auto ignition temps.

Engine exhaust would be great if it didn’t have so much water in it, so… how do we dry the engine exhaust but also keep it hot so it can dry our fuel? A counterflow heat exchanger would do it but, you’d exchange hot wet low oxygen exhaust for hot, dry oxygen rich atmospheric air. Good but not ideal. The heat exchanger would need to be metal b/c the high temperatures would melt plastic. Metal fabrication, sealing and the like would be a challenge, especially for DIY and costly. How do we fix all this in one go?

We have two big pipes filled with rock, say coarse gravel or small stones. The pipes are laid out side by side like some giant double barrel shotgun. I haven’t run the numbers on the right sizing, but sewer pipe and rocks are cheap so going big isn’t costly. Nothing is pressurized and a perfect seal isn’t necessary. Preferably the rocks don’t absorb water easily for reasons that will become apparent; but if that becomes an issue, surface treatment with water glass would fix it (also cheap). You want the pipes to have a large volume for slow gas speeds, plenty of thermal mass, plenty of dwell time for heat transfer.

The big pipes are tipped down slightly from engine side to far side with a drain at the far end. At the end nearest to the engine are baffles that can switch the engine exhaust from one pipe to the other depending on the setting. The baffle directs exhaust gas to one pipe, heats up the rocks in the near end but by the far end the exhaust has lost enough heat that the water has condensed out and cleared through the drain. Over time the rocks heat up and at some point the far end will get hot enough that condensation doesn’t finish to our satisfaction. When that happens, we switch to the other pipe and repeat the process.

Here is the slightly cleaver part. The pipes are joined at the far end so that the cool exhaust comes back through the other pipe making a u turn. After one full cycle using both pipes in turn, the near end rocks in both are hot-hot-hot, while the far end rocks are still cool. When the exhaust gas makes its u turn and travels back through the second pipe will be reheated progressively by the stored heat in the rocks and exits the second pipe at near engine exhaust temps but now it doesn’t have all that water in it, perfect for drying fuel.

You cycle between the two pipes as one gets saturated with heat and the other cools off. Depending on the size of the pipes and the thermal mass it should be some minutes but not hours or seconds. When the gas switches direction you have a slug of exhaust that isn’t well dried so switching frequently isn’t good. The limit for switching slowly is the thermal mass of rock and too much thermal mass will slow the start up time so it is worth avoiding extremes.

So basically, this has the advantages of a counterflow heat exchanger, but it reuses the same gas instead of exchanging it like a heat recovery ventilator would. The regenerators in a Stirling engine serve a similar function and were my inspiration. Stirling engine regenerators must cycle very quickly which is a huge design challenge; we can go slow and slow is a lot easier.

The system builds up heat over time, so you’ll need a “heat sink” at the far end to keep the cool side cool. There are many ways to do this but a water coil would give you free hot (hotish) water and that my head design. Most of the heat that goes in comes out, so the heat sink doesn’t have to work too terribly hard. I have thought a few steps further on various issues like that and their ready solutions. The post is already long so I’ll stop here and follow up if there is interest.

Why am I being such a nutter about super hot drying? Well… I wanted to see if I could torrefy the wood fuel (or close) solely with waste heat and those temps are no joke. I had to push the design pretty hard.